Early history

Ancient games

The Ancient Greeks and Romans are known to have played many ball games, some of which involved the use of the feet. The Roman game harpastum is believed to have been adapted from a team game known as "επισκυρος" (episkyros) or phaininda, which is mentioned by a Greek playwright, Antiphanes (388–311 BC) and later referred to by the Christian theologian Clement of Alexandria (c.150-c.215 AD). The Roman politician Cicero (106-43 BC) describes the case of a man who was killed whilst having a shave when a ball was kicked into a barber's shop. These games appears to have resembled rugby football. Roman ball games already knew the air-filled ball, the follis. activity resembling football can be found in the Chinese military manual Zhan Guo Ce compiled between the 3rd century and 1st century BC. describes a practice known as cuju (蹴鞠, literally "kick ball"), which originally involved kicking a leather ball through a small hole in a piece of silk cloth which was fixed on bamboo canes and hung about 9 m above ground. During the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), cuju games were standardized and rules were established. Variations of this game later spread to Japan and Korea, known as kemari and chuk-guk respectively. By the Chinese Tang Dynasty (618–907), the feather-stuffed ball was replaced by an air-filled ball and cuju games had become professionalized, with many players making a living playing cuju.[citation needed] Also, two different types of goal posts emerged: One was made by setting up posts with a net between them and the other consisted of just one goal post in the middle of the field.

The Japanese version of cuju is kemari (蹴鞠), and was developed during the Asuka period. This is known to have been played within the Japanese imperial court in Kyoto from about 600 AD. In kemari several people stand in a circle and kick a ball to each other, trying not to let the ball drop to the ground (much like keepie uppie). The game appears to have died out sometime before the mid-19th century. It was revived in 1903 and is now played at a number of festivals.

An illustration from the 1850s of

Australian Aboriginal hunter gatherers. Children in the background are playing a football game, possibly

Marn Grook.

There are a number of references to traditional, ancient, and/or prehistoric ball games, played by indigenous peoples in many different parts of the world. For example, in 1586, men from a ship commanded by an English explorer named John Davis, went ashore to play a form of football with Inuit (Eskimo) people in Greenland. There are later accounts of an Inuit game played on ice, called Aqsaqtuk. Each match began with two teams facing each other in parallel lines, before attempting to kick the ball through each other team's line and then at a goal. In 1610, William Strachey of the Jamestown settlement, Virginia recorded a game played by Native Americans, called Pahsaheman. In Victoria, Australia, indigenous people played a game called Marn Grook ("ball game"). An 1878 book by Robert Brough-Smyth, The Aborigines of Victoria, quotes a man called Richard Thomas as saying, in about 1841, that he had witnessed Aboriginal people playing the game: "Mr Thomas describes how the foremost player will drop kick a ball made from the skin of a possum and how other players leap into the air in order to catch it." It is widely believed that Marn Grook had an influence on the development of Australian rules football (see below).

Games played in Central America with rubber balls by indigenous peoples are also well-documented as existing since before this time, but these had more similarities to basketball or volleyball, and since their influence on modern football games is minimal, most do not class them as football.

These games and others may well go far back into antiquity and may have influenced later football games. However, the main sources of modern football codes appear to lie in western Europe, especially England.

Medieval and early modern Europe

The Middle Ages saw a huge rise in popularity of annual Shrovetide football matches throughout Europe, particularly in England. The game played in England at this time may have arrived with the Roman occupation, but the only pre-Norman reference is to boys playing "ball games" in the ninth century Historia Brittonum. Reports of a game played in Brittany, Normandy, and Picardy, known as La Soule or Choule, suggest that some of these football games could have arrived in England as a result of the Norman Conquest.

An illustration of so-called "mob football".

These forms of football, sometimes referred to as "mob football", would be played between neighbouring towns and villages, involving an unlimited number of players on opposing teams, who would clash in a heaving mass of people, struggling to move an item such as an inflated pig's bladder, to particular geographical points, such as their opponents' church. Shrovetide games have survived into the modern era in a number of English towns (see below).

The first detailed description of football in England was given by William FitzStephen in about 1174–1183. He described the activities of London youths during the annual festival of Shrove Tuesday:

- After lunch all the youth of the city go out into the fields to take part in a ball game. The students of each school have their own ball; the workers from each city craft are also carrying their balls. Older citizens, fathers, and wealthy citizens come on horseback to watch their juniors competing, and to relive their own youth vicariously: you can see their inner passions aroused as they watch the action and get caught up in the fun being had by the carefree adolescents

Most of the very early references to the game speak simply of "ball play" or "playing at ball". This reinforces the idea that the games played at the time did not necessarily involve a ball being kicked.

The earliest reference to a ball game that involved kicking comes from 1280 at Ulgham, Northumberland, England in which a player was killed as a result of running against an opposing player's dagger. A similar episode occurred in Shouldham, Norfolk, England in 1321: "[d]uring the game at ball as he kicked the ball, a lay friend of his... ran against him and wounded himself".

In 1314, Nicholas de Farndone, Lord Mayor of the City of London issued a decree banning football in the French used by the English upper classes at the time. A translation reads: "[f]orasmuch as there is great noise in the city caused by hustling over large foot balls [rageries de grosses pelotes de pee] in the fields of the public from which many evils might arise which God forbid: we command and forbid on behalf of the king, on pain of imprisonment, such game to be used in the city in the future." This is the earliest reference to football.

In 1363, King Edward III of England issued a proclamation banning "...handball, football, or hockey; coursing and cock-fighting, or other such idle games", showing that "football" — whatever its exact form in this case — was being differentiated from games involving other parts of the body, such as handball.

King Henry IV of England also presented one of the earliest documented uses of the English word "football", in 1409, when he issued a proclamation forbidding the levying of money for "foteball".

There is also an account in Latin from the end of the 15th century of football being played at Cawston, Nottinghamshire. This is the first description of a "kicking game" and the first description of dribbling: "[t]he game at which they had met for common recreation is called by some the foot-ball game. It is one in which young men, in country sport, propel a huge ball not by throwing it into the air but by striking it and rolling it along the ground, and that not with their hands but with their feet... kicking in opposite directions" The chronicler gives the earliest reference to a football field, stating that: "[t]he boundaries have been marked and the game had started.

Other firsts in the mediæval and early modern eras:

- "a football", in the sense of a ball rather than a game, was first mentioned in 1486. This reference is in Dame Juliana Berners' Book of St Albans. It states: "a certain rounde instrument to play with ...it is an instrument for the foote and then it is calde in Latyn 'pila pedalis', a fotebal."

- a pair of football boots was ordered by King Henry VIII of England in 1526.

- women playing a form of football was in 1580, when Sir Philip Sidney described it in one of his poems: "[a] tyme there is for all, my mother often sayes, When she, with skirts tuckt very hy, with girles at football playes."

- the first references to goals are in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. In 1584 and 1602 respectively, John Norden and Richard Carew referred to "goals" in Cornish hurling. Carew described how goals were made: "they pitch two bushes in the ground, some eight or ten foote asunder; and directly against them, ten or twelue [twelve] score off, other twayne in like distance, which they terme their Goales". He is also the first to describe goalkeepers and passing of the ball between players.

- the first direct reference to scoring a goal is in John Day's play The Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green (performed circa 1600; published 1659): "I'll play a gole at camp-ball" (an extremely violent variety of football, which was popular in East Anglia). Similarly in a poem in 1613, Michael Drayton refers to "when the Ball to throw, And drive it to the Gole, in squadrons forth they goe".

Calcio Fiorentino

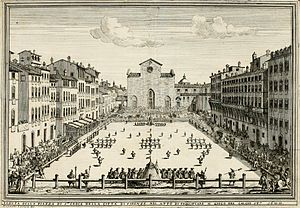

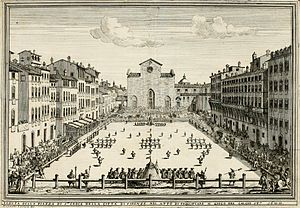

An illustration of the

Calcio Fiorentino field and starting positions, from a 1688 book by Pietro di Lorenzo Bini.

In the 16th century, the city of Florence celebrated the period between Epiphany and Lent by playing a game which today is known as "calcio storico" ("historic kickball") in the Piazza della Novere or the Piazza Santa Croce. The young aristocrats of the city would dress up in fine silk costumes and embroil themselves in a violent form of football. For example, calcio players could punch, shoulder charge, and kick opponents. Blows below the belt were allowed. The game is said to have originated as a military training exercise. In 1580, Count Giovanni de' Bardi di Vernio wrote Discorso sopra 'l giuoco del Calcio Fiorentino. This is sometimes said to be the earliest code of rules for any football game. The game was not played after January 1739 (until it was revived in May 1930).

Official disapproval and attempts to ban football

Numerous attempts have been made to ban football games, particularly the most rowdy and disruptive forms. This was especially the case in England and in other parts of Europe, during the Middle Ages and early modern period. Between 1324 and 1667, football was banned in England alone by more than 30 royal and local laws. The need to repeatedly proclaim such laws demonstrated the difficulty in enforcing bans on popular games. King Edward II was so troubled by the unruliness of football in London that on April 13, 1314 he issued a proclamation banning it: "Forasmuch as there is great noise in the city caused by hustling over large balls from which many evils may arise which God forbid; we command and forbid, on behalf of the King, on pain of imprisonment, such game to be used in the city in the future."

The reasons for the ban by Edward III, on June 12, 1349, were explicit: football and other recreations distracted the populace from practicing archery, which was necessary for war.

By 1608, the local authorities in Manchester were complaining that: "With the ffotebale...[there] hath beene greate disorder in our towne of Manchester we are told, and glasse windowes broken yearlye and spoyled by a companie of lewd and disordered persons ..." That same year, the word "football" was used disapprovingly by William Shakespeare. Shakespeare's play King Lear contains the line: "Nor tripped neither, you base football player" (Act I, Scene 4). Shakespeare also mentions the game in A Comedy of Errors (Act II, Scene 1):

Am I so round with you as you with me,

That like a football you do spurn me thus?

You spurn me hence, and he will spurn me hither:

If I last in this service, you must case me in leather.

"Spurn" literally means to kick away, thus implying that the game involved kicking a ball between players.

King James I of England's Book of Sports (1618) however, instructs Christians to play at football every Sunday afternoon after worship. The book's aim appears to be an attempt to offset the strictness of the Puritans regarding the keeping of the Sabbath.